There was sport on today, so a large portion of my Year 7s were away. As a result, I had an exchange with some of the remaining students at lunch time that went a little like this:

Student 1: We’ve only got 6 students in our class today! [Stretching the truth a fair bit, it was more like 15.]

Me: Okay.

Student 1: So we don’t have to do maths, right?

Student 2: Or if we have to, you can only make us do easy maths.

Unfortunately for them, I had a different idea. Sometimes when a lot of kids are away, it’s necessary to not continue with normal plans so those kids don’t get left behind. However, I still think that having the students that are left with me for 50 minutes is still an opportunity for them to learn.

So today, we looked at intercepts of linear graphs. This doesn’t really arise as a topic until Year 9 under the Australian Curriculum, but given that we’ve been doing a lot of work on solving equations and plotting graphs lately, it seemed like a good idea.

I’m a fan of giving students opportunities to see some of the maths they’ll use in future years, as long as it’s presented in a way that’s not too overwhelming. It allows them to see why we do some of the work we’re doing now, and gives stronger students a chance to achieve at that higher level. And it’s nice to be able to tell parents that their Year 7 child has been working on Year 9 work. 🙂

(I also may have told the Year 10s that they should get working, because the Year 7s were catching up to them…)

This was the process I came up with to let students discover intercepts:

- Define the x-intercept and y-intercept.

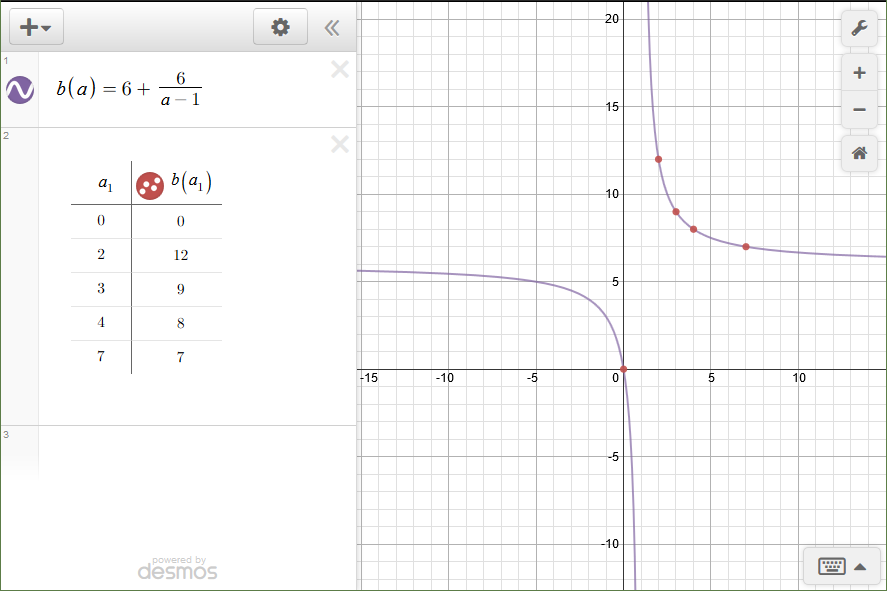

- Use Desmos to find intercepts.

- Notice the pattern in all the coordinates (i.e. there’s a lot of zeroes).

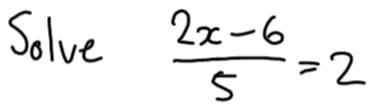

- Have students find x- and y-intercepts for equations using algebra.

- Sketch graphs for those equations. (This is their first time sketching, because it’s the first time using intercepts.)

- Use Desmos to check their graphs.

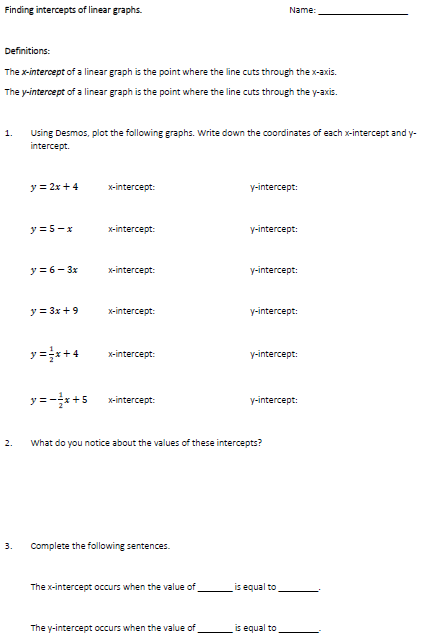

I created this worksheet to for the lesson:

The sheet is purposely vague in places, because I wanted students to figure things out for themselves as much as possible, and where they couldn’t, I could tailor my assistance as needed. Or preferably, they could help each other.

This task seemed to differentiate well, too. Some students needed very clear instructions on how to enter the equations into Desmos and how to read off the intercepts, and had to be reminded which axis was which. But once they did, they found the task fairly easy to follow.

On the other hand, some students recognised what was going on very quickly. I even had one student say, “Won’t all of them have a coordinate with zero?” before she’d even started the task. For these students, the process of finding the intercepts with Desmos was a way to verify the results they predicted.

You can download the worksheet here:

- PDF: Linear graph intercepts.pdf

- Word document: Linear graph intercepts.docx