Year 7 are currently working on solving equations with pronumerals for the first time. Specifically, we’re using backtracking to solve multi-step linear equations.

This year, I realised there’s a problem with getting students to understand backtracking. Before I can expect students to work backwards through steps to solve an equation, I need to make sure they understand how the equation goes forwards. I think that in the past I’ve been too quick in jumping into backtracking, without spending time on fortracking (I know that’s not a word, but I’m running with it).

I’m at an advantage over my students when they see an equation I’ve written. I’ve seen the entire process. I started with a variable and its value, then I applied a number of steps to build it into an equation. Then I know that the solution can be found by working backwards through those steps.

But students only see the last part of that process. And while a few students can look at that equation and see the steps hidden in it, many have no idea where the equation comes from or what it represents. My solution: pull back the curtain, and let students see the entire process themselves.

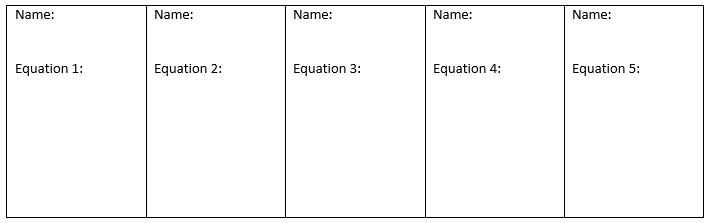

I created this worksheet for “building equations”:

After I gave and example, each student create five equations. Then, they wrote the final equation and their name in one of these boxes along the bottom of the page:

Then each student gave their equations to other students, who then glued them in their workbooks. The plan was for those students to solve these equations, but this had to be left to a later lesson, as the “building” part of the task took longer than I expected.

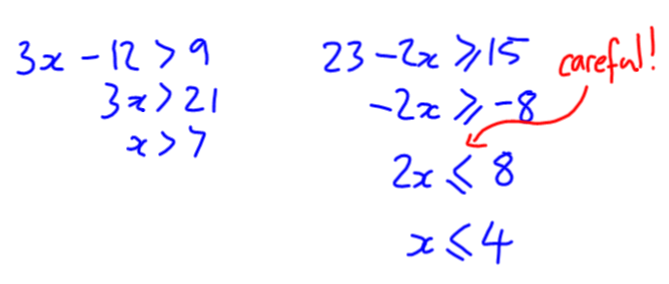

This was okay, as it allowed me do identify weaknesses a number of students had, particularly with the order of operations. One student ended up with 3(x + 1) in their equation, despite wanting to do the multiplication by 3 first. It seems they realise that parentheses have a role in deciding order, but are confused about how they work.

I started the activity by getting the class to talk me through an example, which students copied onto their sheets:

[An aside for me to remember later: Some of my kids seem to be amused by problems that involve using the same number repeatedly, hence all the threes. But in copying it here just now, I realised that (3j – 3)/3 is, of course, just j – 1. But also, (nx – n)/n is also x – 1 for any n. I wonder if there’s some activity I can create that involves exploring that fact?]

If you want a copy of this worksheet, you can find it here:

- Word document: Building equations.docx

- PDF: Building equations.pdf