So Year 12 are gone and finished their exams a few weeks ago. I always feel a little sad saying goodbye to my Maths Methods students. I have so much fun with them and get to know them pretty well over the year, and this year was no exception. One thing that was different was the fact that I lost the competition we have over the year. Well, if I really wanted to I could claim the win on a few technicalities (drawing on my posters on muck-up day should’ve cost them a few points), but I’ll let it slide.

They decided that if they won, their prize would be getting to write a blog post for me, so this is it. I’m trying to resist the urge to clarify and explain a lot of their comments. Just be aware that some of the things they say might not be 100% accurate… 😉

Next year is not looking good. I’m already down 4-0 after one week of headstart classes…

Mr Carter’s assessment report

Stop

- Looking for your favourite class, you found them this year.

- Giving yourself points for no reason.

- Whinging about hockey injuries, only to find out they don’t exist.

- Giving yourself eighteen points in a lesson as a final attempt to regain dignity in the class competition, no one likes a bad sport.

- Forgetting to bring your laptop charger to class, those minutes of absence, added up might have changed our scores by one or two marks, changing our ATARs, changing the outcome of our future.

Start

- Being fair when awarding points, it’s not “discouraging class participation”, it’s playing strategically.

- Telling students when you are going to be away.

- Preparing students for exams in term one, then they might have a chance.

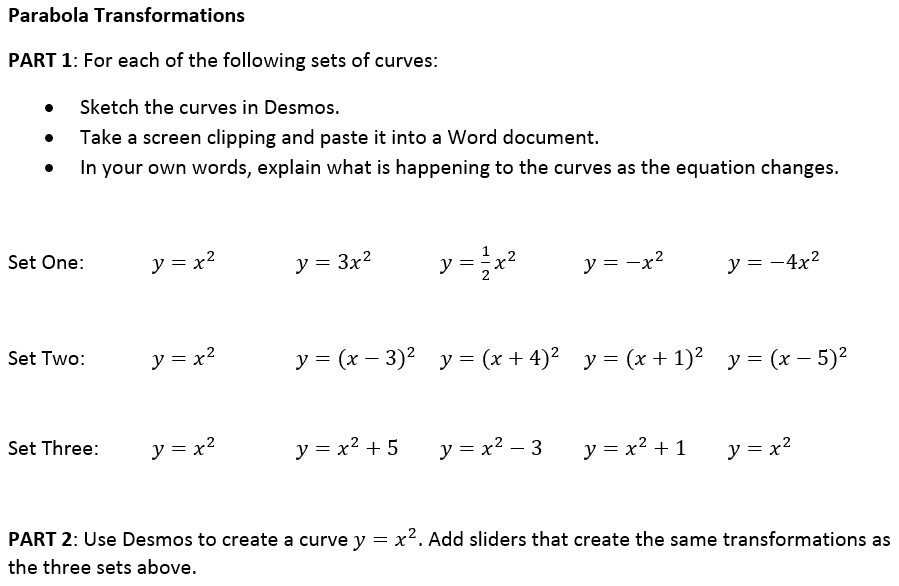

- Removing sections from the textbook from your study list, particularly: algebraic techniques, functions and graphs, transformations, algebra of functions, differentiation and anti-differentiation, graphs and modelling, discrete and continuous random variables, and the normal distribution. So basically everything.

Keep

- Encouraging students to do maths, but not specialist, that’s just silly.

- Teaching methods so that students don’t have to suffer through distance education.

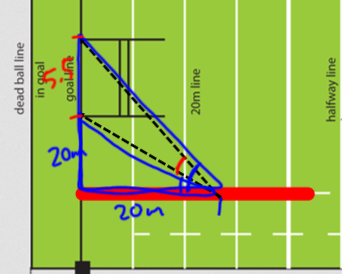

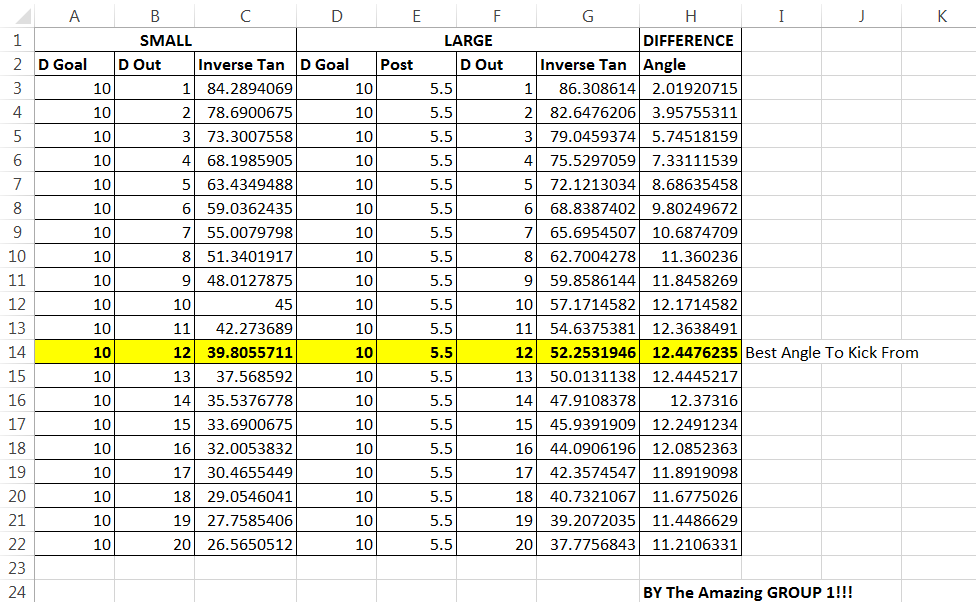

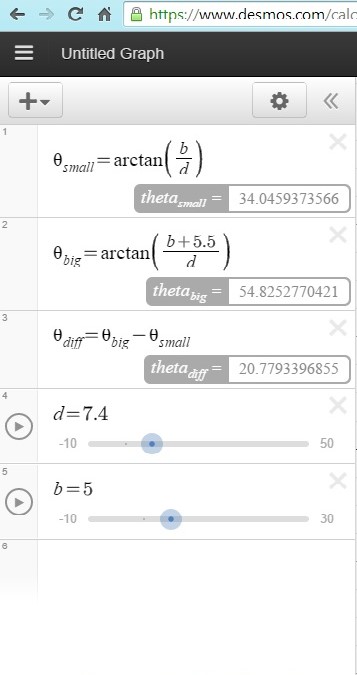

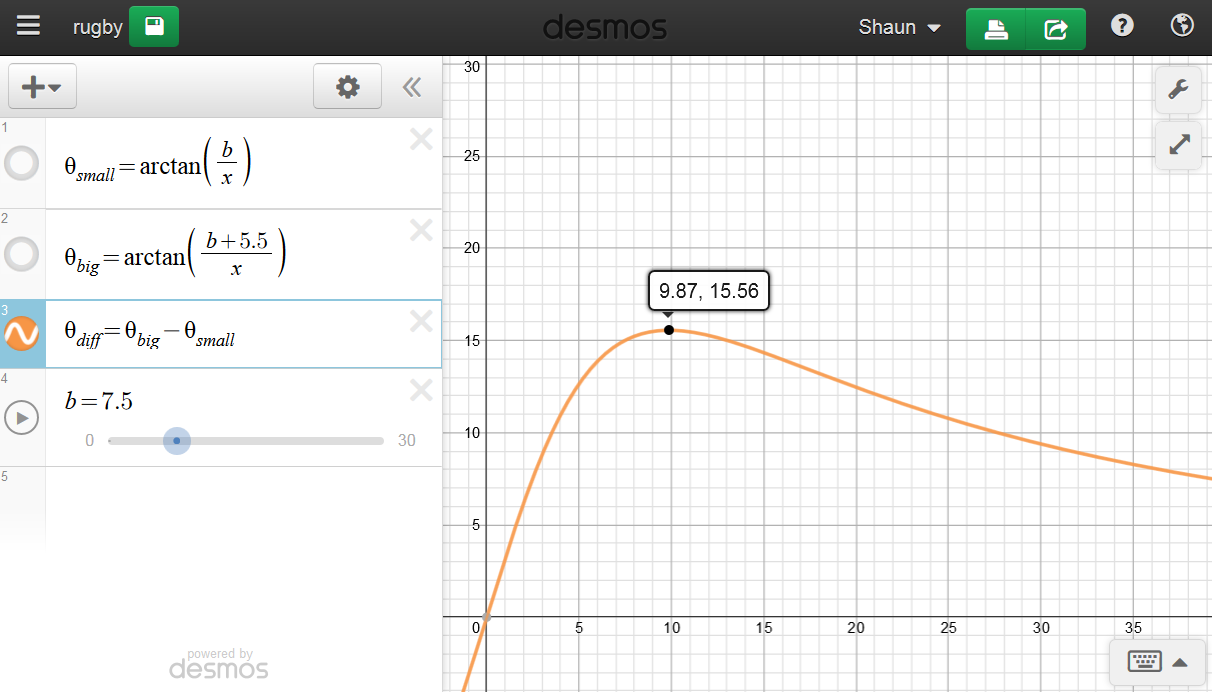

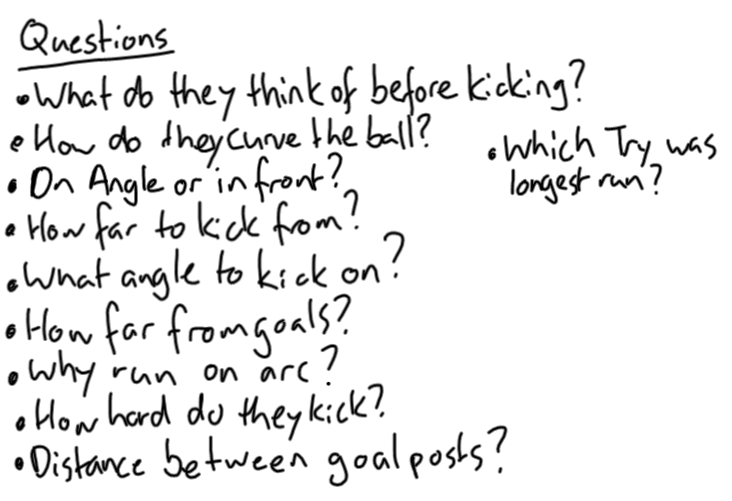

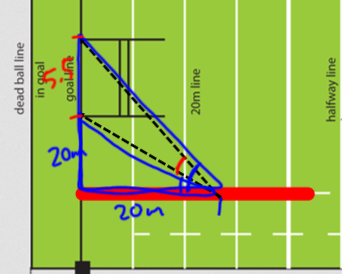

- Diverging from the maths question you were asked to interesting topics, so that despite students not doing any textbook questions for the lesson, they continue to learn.

- Telling (rubbish) maths jokes, they’re not funny, but at least you tried.

- Telling us how methods can be used in real life, it gave us some hope that the 146 hours we spent in that room this year will be worth it.

Change

- Your lesson plan so there is cake every Wednesday, and so we don’t have a double on Friday afternoon.

- The way you spell chai in the methods probability SAC, it’s not spelt chi.

- The computer for which the license agreement for the CAS software is on, we feel that the five seconds that it takes for you to click on the ‘continue free trial’ button is a major disruption.

- Your career guidance strategies, you’ve successfully convinced us to never become a maths teacher.

Even after all our comments, you are, and always will be our favourite 3/4 maths methods teacher that we ever had, just as we were your favourite methods class. Deep down we did sort of like methods, we just wanted to take this opportunity to whinge about is this one last time, and at least it was better than English (in our reality). So thank you, Mr. Carter, for being our final maths teacher, and for making methods as enjoyable as you could.