One of the most exciting things in maths is realising a connection you didn’t see earlier. Hopefully this experience is what we’re giving students all the time, but as teachers we get it too. And sometimes, the connection seems so obvious (to someone with a maths degree), that’s it’s a little embarassing when you realise you didn’t notice it before.

Did you know that the volume of a pyramid (or cone) is one third of the volume of the equivalent prism (same base and height)?

Yeah… I didn’t know this until recently. I knew the formulas for the volumes of pyramids, and even derived them using calculus, but I’d never made the connection between them and prisms before.

I wanted to give my students the opportunity to make the same discovery. My school has a set of clear plastic prisms and cones, each with coloured plastic inserts of the net of the shape:

It took me a while to find these. I knew they existed because I remember them being bought, but everyone I asked didn’t know where they were. Well, it turns out the first colleague I asked did know where, but I was terrible at describing what I was after. Oops.

They come in matching pairs of the same colour and base, and they all have the same height. The only difference in each pair is that one’s a prism and the other’s a pyramid. I split the class into groups, and gave each group a pair without saying anything about them.

I asked the class to describe what they noticed about them. “They’re the same colour,” was the first reply. Okay, ask an obvious question, get and obvious answer. But after that, we get a few more suggestions:

- Each group had a prism and pyramid (or cylinder and cone – that group was very quick to point out every time I forgot to clarify that).

- The prism and pyramid in each group have the same base.

- The net of the prism has one more face than the pyramid. Even though this wasn’t the objective of the lesson, I loved this! The group that suggested it even gave an explanation why. One student from another group then said that if the base has n sides, then the pyramid has n + 1 faces and the prism has n + 2. Hooray! 🙂

- The shapes have the same height.

- They’re made of plastic (okay, not all of them were that noteworthy).

We’d already covered the volumes of prisms at length, so I asked them to look at the pyramid and think about how that volume compares. I gave the groups time to discuss. Interestingly, they all came back with the same answer – half the volume. Most groups had a reason too. One group said they thought if the pyramid was placed inside the prism, the volume outside the prism would be the same as the inside. Another said that the pyramid is like a triangle, and a triangle is half a rectangle.

I’m increasingly seeing the value in “wrong” answers. It was great that, even though the volume is not half, they were still able to give reasons. But also, no-one was completely happy with their answer. They thought it made intuitive sense, but weren’t satisfied without proof. Awesome 🙂

So, it was time to test it. I forgot to mention I did this lesson in the Science room, so there were sinks conveniently close by. The class realised that if their conjecture was true, they should be able fill the prism with water by filling the pyramid twice. So, they got to work:

Hmmm, this doesn’t really look half filled.

A filled prism.

Putting the shapes back together. You can also see this student’s formula sheet and their part-finished “New Things” page from this lesson.

Surprise! They all found they could fit three pyramids inside the prism.

Next I had students write down a formula for the volume of a pyramid/cone. They already knew the volume of a prism, so they used that to work out the pyramid. The nice thing about this (as opposed to them copying a formula off the whiteboard) is that they each wrote down the formula how they wanted. Some used ÷3, some wrote it as a fraction, some wrote 1/3 in front. But they all wrote a formula they were comfortable with and understood.

Areas for Improvement

I was really happy with how this lesson went, but I wasn’t particularly pleased with the end. We found correctly that the volume was one third, but we never really justified why.

I mean, sure, for a scientist, the empirical evidence gathered was fantastic. But we’re mathematicians, darn it. Aren’t we suppose to hold ourselves to a higher standard?

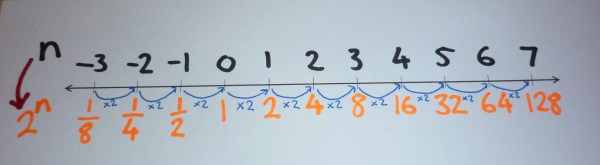

Does anyone know a decent way to explain why it’s a third, without relying on integration – this is a Year 9 class after all. Using calculus is such a nice proof, and also explains why changing from 2D to 3D changes from half the area to one third the volume. But I’m struggling to think of another explanation.

The class really enjoyed this lesson, as did I. But this one loose end is still bugging me.