(Quick confession: this was actually weeks ago. I’m not sure why it took me this long to get around to blogging it.)

Why do textbooks bother trying to explain concepts before each exercise? The kids don’t read it, I don’t refer to it. And the explanations take all the fun of doing mathematics out of it.

In case anyone wants a more pedagogically solid complaint than “takes out all the fun”: The book just gives students formulas and expects them to rote learn their use, rather than using discovery to build understanding.

Anyway, case in point: the area of a sector. The book basically says, “sectors, here’s a diagram, here’s the formula, go do questions.” I thought I could do better.

Enough with the textbook ranting, do some maths already…

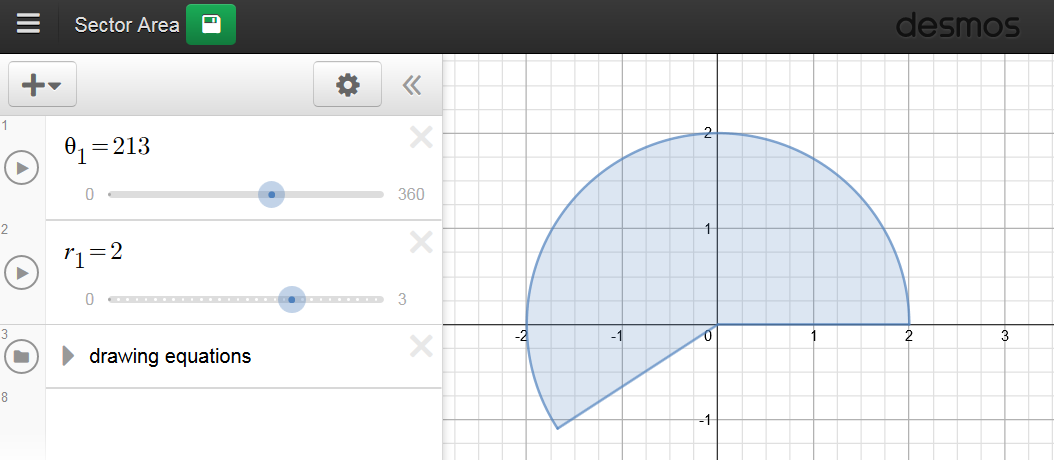

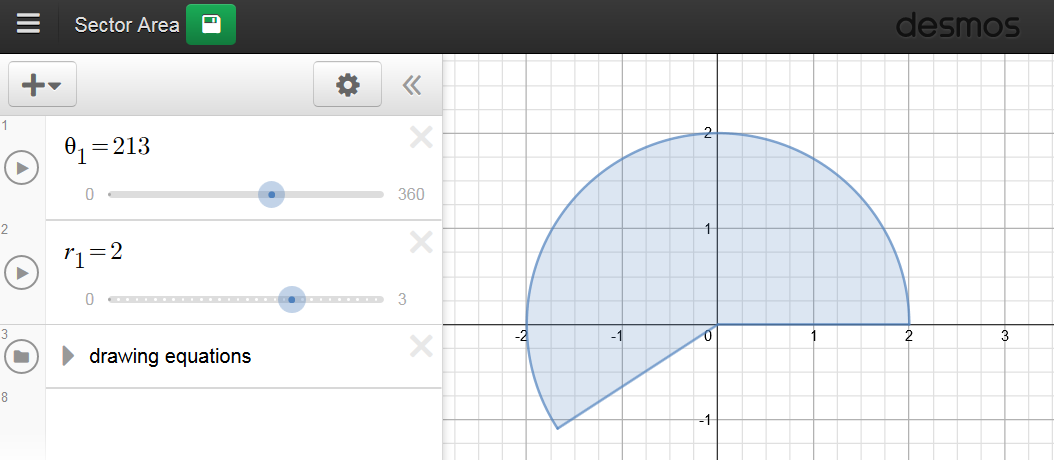

Normally this would’ve been something I’d use Geogebra for, but since I’ve become more than a little obsessed with Desmos lately, I went with it instead and put this together:

[Update 2/2/18: In more recent years, I’ve used another version of this that does both sector area and arc length. You might find that more useful. Link is https://www.desmos.com/calculator/mybwxhjws3.]

I started with the whole circle displayed on my IWB, and we talked about the effect of changing the radius on the area. This was revision, but I wasn’t particularly satisfied about how this discussion went – they got the idea that, say, doubling the radius quadruples the area. but when they gave reasons they only talked about r2. They couldn’t connect it to the circle itself. I moved on at the time, but I think I should’ve spent more time developing the idea.

So I changed the angle to 180°, and asked what the area would be now. “That’s easy, half the area,” came back the response. I showed them a few more angles: 90°, 270°, 45°. They responded with the appropriate fractions. So far so good.

“So what about 213°?” That had them stumped. “Well, maybe you should figure it out in your groups?” (Forgot to mention, I already had them in groups.) I gave them the link to open the Desmos file on their laptops to play around with while they discussed.

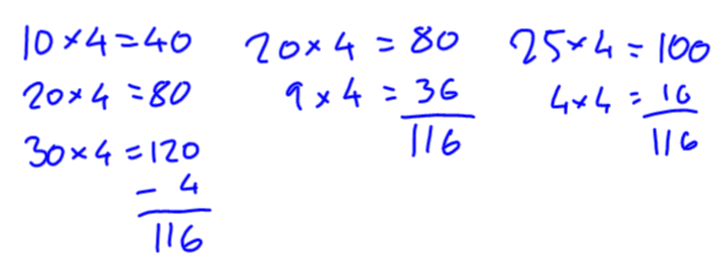

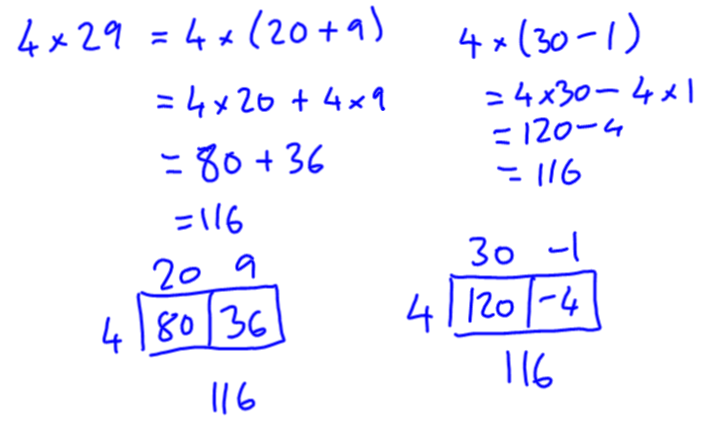

What I love is that there were different methods found around the room. Some found the fraction 213/360 quickly, but there were other approaches. Some found the area with 1°, then multiplied by 213. Some recognised that 213° is between 180° and 180° + 45°, and used that fact to determine lower and upper bounds on the solution.

This was a nice activity to differentiate, too. When some individuals found the solution quickly, I had them figure out the formula themselves. When they thought they had it, I made them explain it with their groups, who then discussed whether it worked or not. Others needed more time to find the area in the first place, but they all got there in the end.

I then had each student create three different sectors using the Desmos sliders, which they then printed, stuck in their books and calculated the areas for. (The nice legacy of being in the former computer lab is having a printer in the room!) A few switched on students who had figured out the formula typed it into Desmos so it just calculated the area for them. I never told them how to do this! They thought they were so clever for “cheating” this way 🙂

Bonus features!

A few random tangents I thought of while writing this (I mean discussion tangents, not the … oh, you know what I mean.)

A couple of tech tips for you: To get the images of the of the sectors, I showed students the “Snipping Tool”, a feature of Windows 7 and 8 (and maybe earlier? I can’t remember when it came in.) I’m always surprised by how few people know about this. Everyone knows “Print Screen”, but that’s the old way to get screen images. If you only want part of the screen, Snipping Tool lets you drag a rectangle around only that part! So much easier than having to crop it after.

And my second tip: the easiest way to find it is hit the windows key, type “snip” and hit enter. And this works for any program! You don’t have to waste time searching the start menu/start screen to find that program you want if you know the name of it. Just hit the windows key, start typing the name of the program you want, then hit enter when it comes up. Works in Windows 7 and 8. Again, not enough people know this.

Ed-tech startups: listen, if you want teachers to actually use your product, follow the example of Desmos: make it easy to use, work on pretty much every device (preferably in a browser), easy to share with students, don’t require student logins and don’t make teachers create a new account to use it (use Google, Twitter, etc. to login). If I need to jump through hoops to use your product, I’m not going to bother.

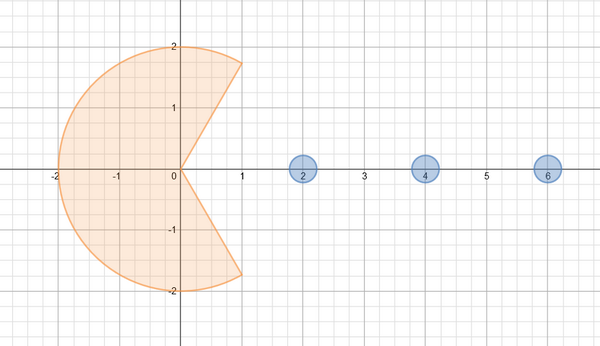

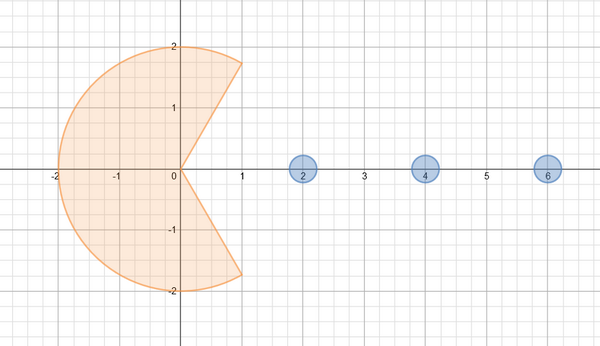

I’ve already shared this on Twitter, but you can’t draw a sector without thinking of Pac-man (or maybe pizza). So, I got distracted for a while and made this. (It’s actually animated of you follow the link!)