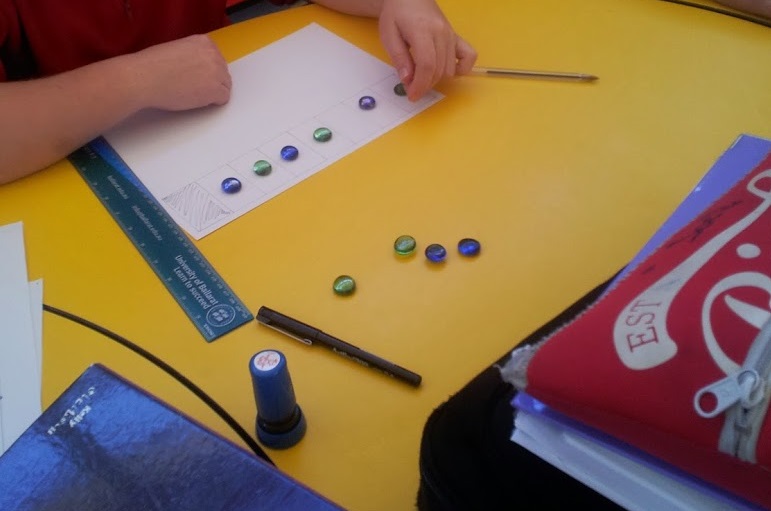

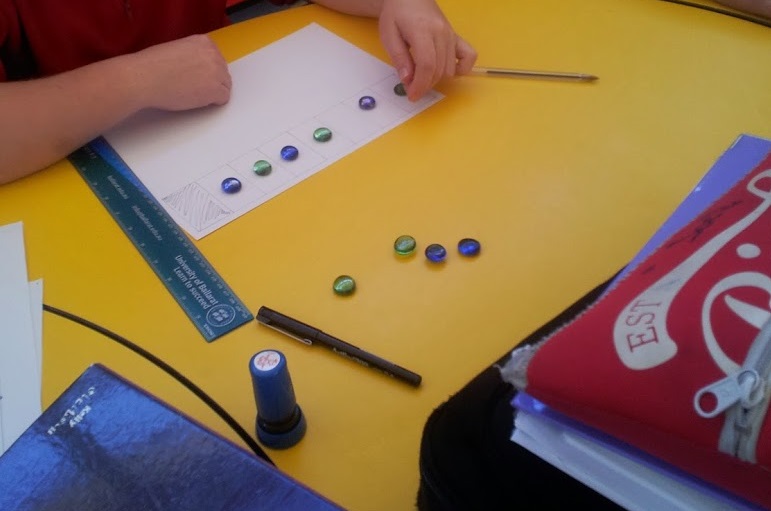

So, I think a lot of people will be familiar with this puzzle. Start with an arrangement like this:

The aim is to swap the positions of the green and blue counters. The counters can move either one or two spaces forward, and each space can contain only one counter.

I was given the idea to use this in class at a PD a couple of years ago. The puzzle still works with any number of counters on each side, it just takes more steps to complete it. In fact, the number of steps forms a very nice algebraic pattern.

We did this activity on Monday. I added a silly story about two families of kangaroos trying to get past each other on a small path. (Now that I think about it, frogs would’ve made more sense with the colours we used. It probably wasn’t necessary at all anyway.) Initially, the class struggled to work out how to solve the puzzle. A few students excitedly called me over because they’d “worked out how to do it!” But when I asked them to show me, they’d forgotten. But that’s OK, this helps reinforce the idea that getting the answer is not the same as understanding the problem.

After a little while, I suggested they try the puzzle with only one counter in each group. “That’s easy!” they all said. OK then, try it with two.

(Sorry for the ugly black blob, but that student had written their name on their hand in black marker, for some reason.)

Slowly, kids around the room started to figure it out. Once they knew how to solve the puzzle, I had them count how many steps it takes to solve. They then added more counters and counted those steps.

“How many steps will it take to solve with 56 in each group?” I asked. They thought I was crazy (maybe past tense isn’t right for this sentence…). Their first thought was that I wanted them to physically solve the puzzle with that many. “Well, maybe there’s a pattern we can find, instead.”

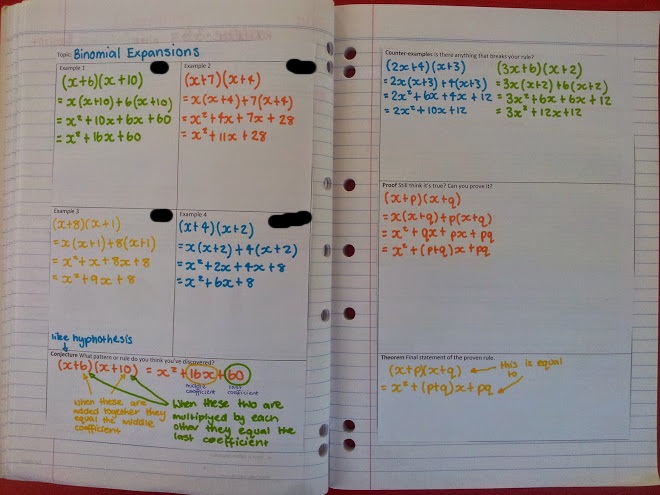

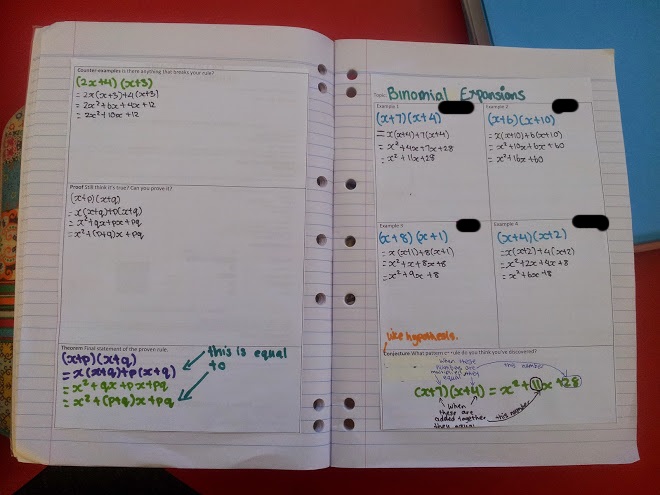

So they drew up tables comparing n (the number in each group) to the number of steps. Two different patterns were spotted: multiply n by the number two bigger than it, or multiply n by itself and add double n. Of course, when they wrote the patterns as algebraic expressions, the following result emerged:

n (n + 2) = n2 + 2n

To check our results worked, we completed this table on the whiteboard:

(And now I’ve revealed to the world just how horrible my handwriting is…)

We never did it, but the next step would be explaining why this pattern works. The nice thing about this is that while n (n + 2) is the easier pattern to see, n2 + 2n is easier to explain (each blue counter passes each green counter once, plus the extra small step each counter makes).

What I like about this lesson: Expanding and factorising are fairly abstract concepts for high school students. This activity makes them more concrete, without trying to make up a “real world” application that doesn’t really exist. I’m enjoying that so far this term, I haven’t been asked the dreaded question, “When are we going to use this?”

Some of the class still wanted to do the puzzle with 56. I should’ve seen that coming – this same class in Year 7 wanted to confirm that 1 m3 = 1 000 000 cm3 by collecting every 1 cm3 block from the primary classrooms and stacking them into a giant cube. They still want me to ask if we can drain the town pool to measure the volume of it. I love this class – always curious and creative but no sense of practicality.

Update (April 2016): I’ve coded an online version of this puzzle. See my blog post about it at https://www.primefactorisation.com/blog/2016/04/14/interactive-jumping-puzzle/