We have one week to go, which means one thing. Okay, it really means a lot of things, but I’m thinking of one thing in particular. Certain students are just realizing what I’ve been trying to tell them all year. Their grade is not high enough and they’re going to have to retake a whole bunch of quizzes before the end of the year if they want to pass.

Let’s try and make this a bit more positive. There’s also a large contingent of students trying to turn Cs into Bs, Bs into As, and even some trying to turn 99% into 100%.

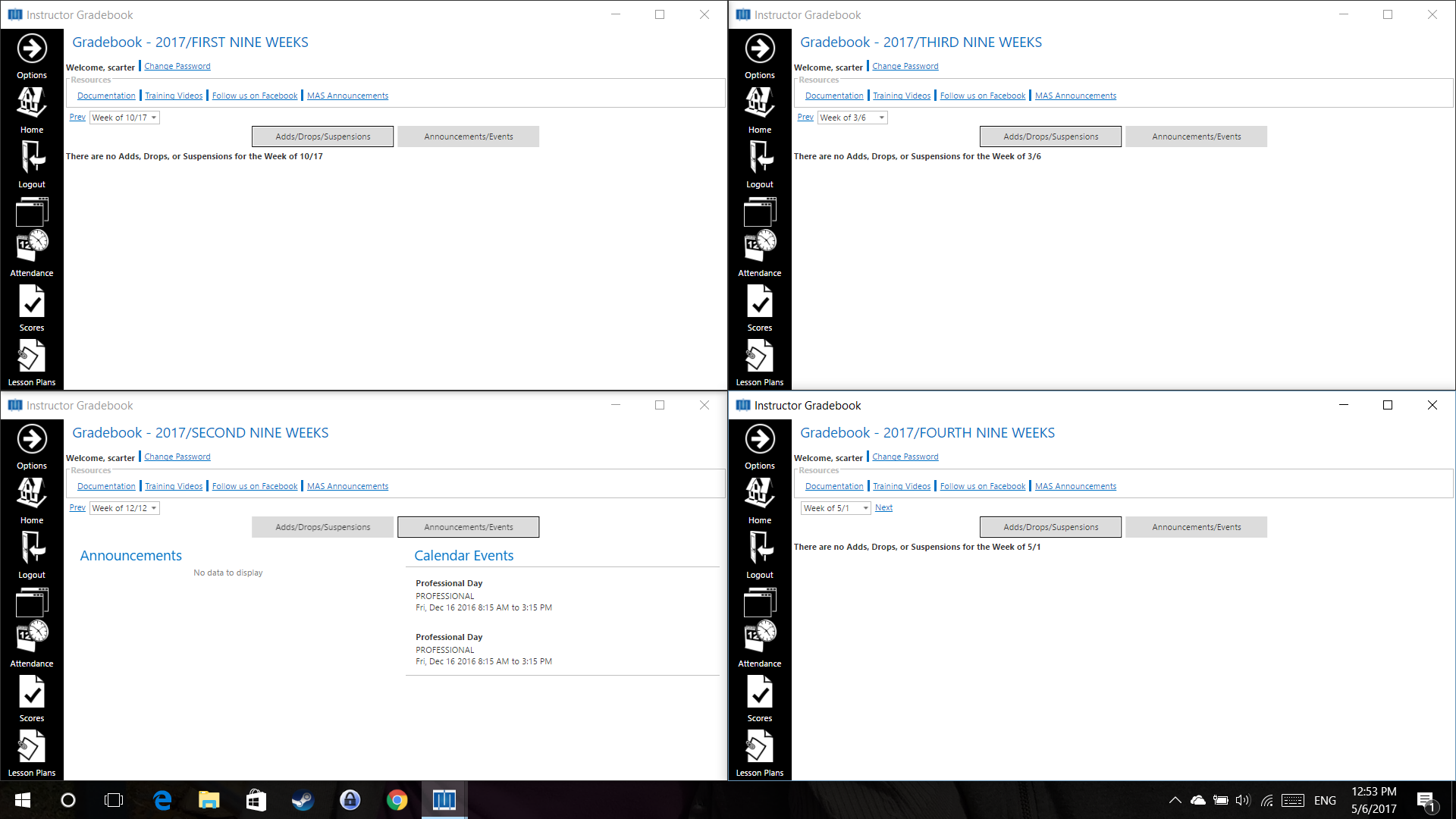

Whichever way you look at it, one result is that I have to spend a lot of time with my gradebook, entering quiz scores from random times throughout semester 2, and fielding requests from students to know their grade. The software my district uses doesn’t make this the easiest thing to do. It separates each “Nine Weeks” and makes switching between them annoying, taking a few seconds of loading time and completely resetting the view I had open just before. Throw in that the same thing happens if I want to enter attendance, and that adds up to a lot of wasted time. My solution to date has been to open multiple web browser tabs with a different view in each. But that makes my browser cluttered and remembering which tab is which among all my other tabs becomes difficult. Not to mention, the address bar and tabs take up valuable space for seeing students and their grades.

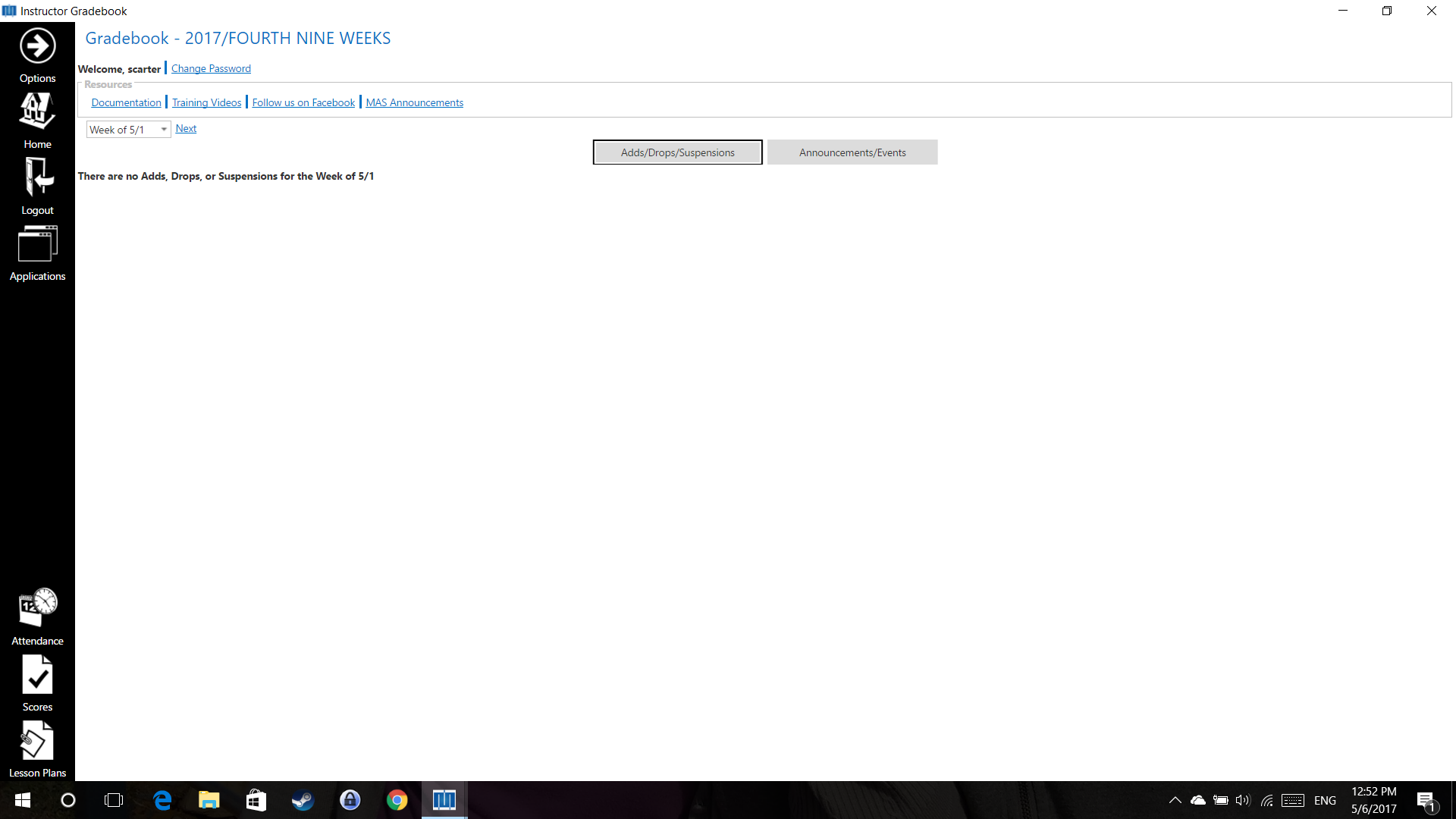

I’ve come up with a solution. Google Chrome has a feature that can turn any webpage into a standalone web application, which is displayed as a separate window with a title bar and nothing else. It appears as a separate app on the taskbar (in Windows at least), which means it doesn’t get mixed up with the rest of my random web browsing. The software my district uses is Wengage, but this applies equally to any gradebook you can access through Chrome (I haven’t tried this with other browsers, but they might do something similar.)

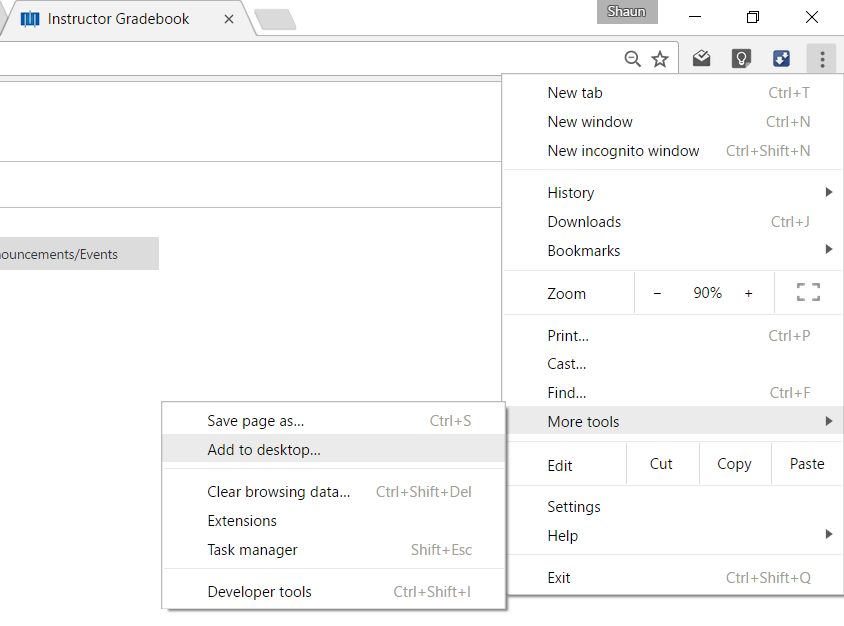

To do this, navigate to the page you want to make an app in Chrome. Click the “three dots” button (I’m sure Google give that a proper name) and select More tools, then Add to desktop…

This will put an icon for your new app on your desktop (unsurprisingly).

Double click that icon to open the app! If you want, you can find the option to “pin” the taskbar icon (keep it there even when the app is closed) by right clicking it.

To be honest, it really is just a chrome tab that looks a bit different, but that’s exactly what I wanted. By appearing as a separate window, it’s out of the way but easily accessible. If you want multiple windows (say, one for grades and one for attendance) hold the shift key while you click the taskbar icon. (Useful tip: this works for almost all Windows programs.)

Is this going to revolutionize the way I manage grading? No, not even slightly. But it has made something I find annoying into something slightly less annoying. Which, to be honest, is exactly what I need as a teacher sometimes.