I’m becoming a student again this fall. As I’m preparing for that, I’ve been reading through some of the textbooks for the classes I’m taking, which has got me thinking about how we use the word “range”.

I’m talking about the range in the context of functions. The fact that I’m even having to clarify that I’m not talking about statistics, or an interval of integers, or the multitude of uses the word has outside of math, highlights just how ambiguous the word already is, without mentioning the ambiguity just within the context of functions!

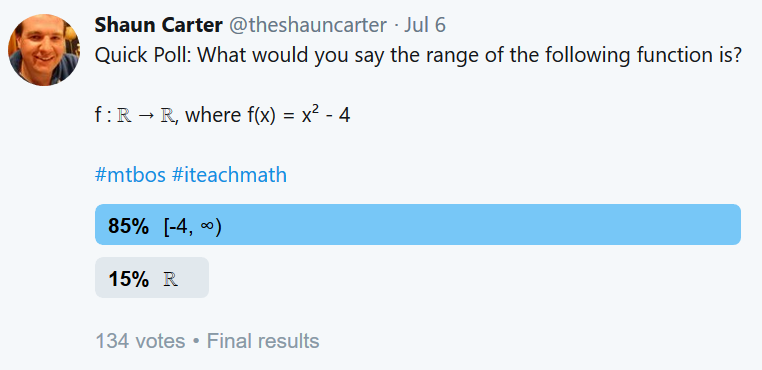

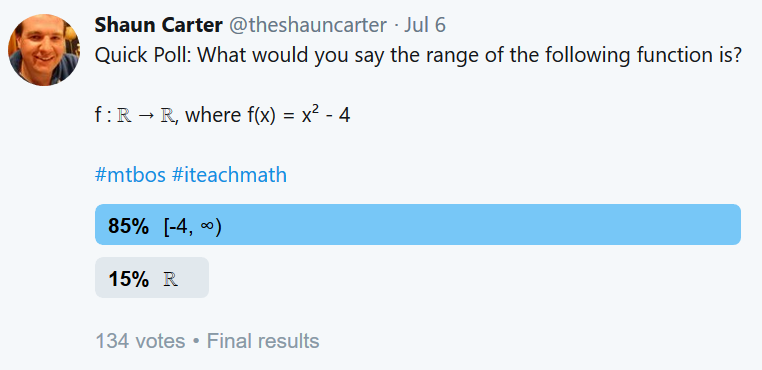

To highlight the problem, I posted this poll on twitter last week:

The correct answer to this question is… well, there isn’t one. It is a (deliberately) bad question because the meaning of “range” is unclear.

The question I was really asking was “Does the word ‘range’ refer to the image, or to the codomain, of a function?” And while most said that it refers to the image (which is what I would’ve said, prior to thinking about this), 15% chose the codomain.

The problem is illustrated really well by this image from Wikipedia. The is domain is red, the codomain is blue, and image is yellow. But the range is either yellow or blue, depending on context. According to my poll, and the limited research of high school standards I’ve done, most would say yellow. But definitely not all agree with that.

That Topology book that I mentioned earlier uses the term “range” to refer to the codomain, and uses “image set” for the image. But, there is also a footnote stating,

Analysts are apt to use the word “range” to denote what we have called the “image set” of f. They avoid giving [the other set] a name.

Maybe the 20 people who all voted for ℝ were all topologists? Probably not. But, it shows that different people have different assumptions about what the range of a function means.

With all of this confusion around the meaning of the word, how are high school students supposed to understand what the range is? One solution would be to get rid of the word altogether. The words image and codomain already describe the two sets without any ambiguity, so we can just use those instead, right? We just need to define the two terms clearly, and the confusion in our classrooms will be significantly reduced.

Alas, students are still going to come across the range, whether that’s in a textbook, on a standardized test, or in their next class with another teacher. But there’s somewhere else we can turn for guidance. I’m a strong believer in the idea that whatever academic standards apply to your jurisdiction, you should follow them, regardless of your opinion of those standards. So if your standards use the word range, your class should too. I took a look at a few different standards to examine how they suggest the terminology of functions should be used.

Common Core is a bit of a disappointment here. The glossary does not define range, domain or even function. The standard CCSS.Math.Content.HSF.IF.A.1 states that a function “assigns to each element of the domain exactly one element of the range.” Which is an accurate description of a function, but it’s unclear if the range here refers to the image or the codomain.

Oklahoma (where I’ve taught most recently) defines the range in the context of relations, rather than functions: “The set of all the second elements or y-coordinates of a relation is called the range.” Now, this is not how I would’ve written this definition, but it is something we can work with. By this definition, the only values in the range are those that have a matching value in the domain, meaning the range is identical to image. If I were teaching high school classes again this year, I would teach the range as I have previously, but I’d also take the time to define the codomain as well.

The Australian Curriculum gives a nice, clear definition of the range, which matches the image, as well as defining the codomain, in the glossary for Mathematical Methods, under the heading “Function”. I don’t remember teaching the codomain explicitly when I last taught in Australia. Perhaps I should have.

Regardless of where you are, I’d argue that it’s important to define the range very clearly, according to your location’s standards. But also define codomain or image, depending on how range is defined.

The point I’m trying to make is this: As math teachers, we need to constantly examine the terminology we introduce to our students. Because sometimes we might not be being as precise as we could be. If you want your students to be really clear on the meaning of mathematical terms, make sure you are first.